What Happened to Black America After 1964?

When the 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed, it was supposed to be the beginning of a new era, freedom, opportunity, and dignity for Black Americans. And in many ways, it was. But beneath the surface, something else began to shift.

The Black community went through a massive cultural transformation, one that still shapes our neighborhoods, our families, our music, and even our faith today. Hip-hop and rap emerged as powerful (and sometimes dangerous) new art forms. But alongside the creativity came a moral decline, a breakdown of the family structure, and a rise in single motherhood and unemployment among Black men.

Integration opened doors, but it also pulled the Black community away from the one institution that had held us together through slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation: the Black church.

As the church lost its central role, new belief systems, the Black Religious Identity Cultures (BRICs), rose, offering alternative identities, alternative gods, and alternative explanations for Black suffering. These movements reshaped how many Black people saw themselves, their history, and their relationship with Christianity.

The Church: The Heartbeat of Black America

Before 1964, the Black church wasn’t just a place to worship; it was the center of Black life.

It was the bank when white banks denied loans. It was the school when public schools were segregated. It was the job center, the social service hub, the political headquarters, the counseling office, and the community’s moral compass.

During slavery and Jim Crow, the church kept hope alive. It taught that Jesus was a deliverer, a protector, a liberator. It reminded Black people that God saw their suffering and would one day bring justice.

Even the first major slave rebellion in the U.S., Nat Turner’s rebellion, was fueled by Turner’s belief that God would deliver enslaved people just as He delivered Haiti. Christianity wasn’t a tool of oppression; it was the spark that ignited the Civil Rights Movement.

But after 1964, when integration made resources more accessible, many Black people stopped depending on the church. And when the church stopped being the center, something else rushed in to fill the void.

Why Did the Church Lose Its Power?

By the mid-20th century, new Black identity movements began questioning Christianity. They argued that the faith of our ancestors was a “slave religion,” even though history proves the opposite.

After integration, the church no longer felt responsible for providing every resource, and many Black people no longer felt the need to seek the church for guidance. At the same time, new social issues, sexuality, gender roles, and economic inequality, caused tension between the church and younger generations.

Instead of turning to Scripture, many turned to new belief systems that promised empowerment but often led to confusion, division, and moral decline.

Who Are the BRICs?

After the Civil Rights Act, when the Black church began losing its central role, new movements rose up to fill the void. These weren’t just religions; they were identity-shaping cultures. Collectively, they became known as the Black Religious Identity Cultures (BRICs). They promised empowerment, pride, and a sense of belonging, but often pulled people away from the teachings of Christ.

These groups spoke directly to Black pain, anger, and the desire for liberation. They gave new names, new gods, and new explanations for why Black people suffered. But while they attracted thousands, they also created division, confusion, and moral decline in the community.

Let’s break them down:

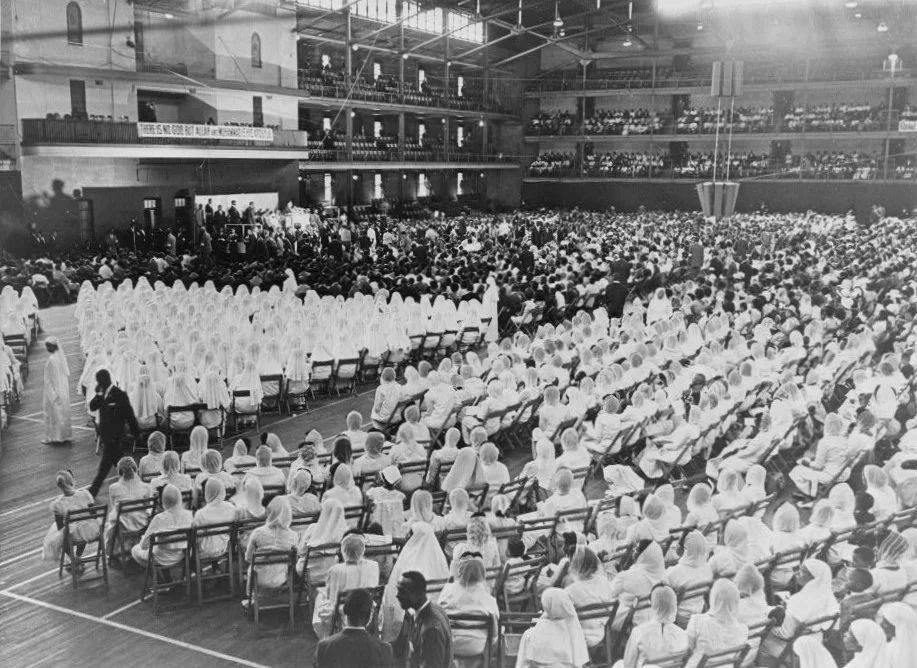

Nation of Islam (NOI) - Founded in 1930 by W.D. Fard, the Nation of Islam mixed Islamic teachings with Black nationalist ideas. It taught that God was a Black man, the first man created 60 trillion years ago. White people, according to NOI, were “devils” created by a rogue scientist named Yakub, given dominion for 6,000 years. That dominion, they claimed, would end in the 20th century.

By the 1950s, Malcolm X had become the face of NOI, electrifying crowds with fiery speeches about Black pride and independence. The Nation rejected the “turn the other cheek” philosophy of the Civil Rights Movement, calling integration weak. Instead, they pushed for self-sufficiency, Black-owned businesses, schools, and communities.

By 1964, NOI had over 300,000 members and was distributing half a million copies of its newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, every week. For many, it felt like a revolution. But for others, it was a rejection of the gospel of Christ.

Hebrew Israelites - Emerging in the late 19th century, Hebrew Israelites taught that Black Americans were the true descendants of the biblical Israelites. Leaders like William Saunders Crowdy and Frank Cherry preached that white people were hated by God and evil, and that Jesus would return in the year 2000 to usher in a race war that would elevate Black people over whites.

By the 1960s and 70s, this movement gained traction, offering Black people a new identity rooted in Scripture but twisted away from the gospel. It gave many a sense of divine destiny, but also fueled hostility and division.

Moorish Science Temple of America (MSTA) - Founded in 1913 by Noble Drew Ali, MSTA taught that Black people were not Africans but “Asiatics,” descendants of ancient Moabites from Morocco. Ali claimed Allah had given him a mission to spread Islam among African Americans.

Members were told they could no longer practice Christianity. While MSTA didn’t demonize whites, it forbade interracial marriage and pushed for peaceful coexistence. Between 1926 and 1929, the movement expanded rapidly, reshaping how many Black people saw their roots and identity.

Five-Percent Nation (Nation of Gods and Earths) - In 1964, Clarence 13X (known as “Allah the Father”) broke away from the Nation of Islam. He taught that the Black man was literally God personified. According to his teachings, 10% of people knew the truth and used it to control the remaining 85%. The last 5%, the “Five Percenters,” were those who knew the truth and sought to enlighten the masses.

By the 1990s, Five-Percenter ideology had deeply influenced hip-hop. Artists like Rakim, Nas, and Wu-Tang Clan wove their teachings into their lyrics, spreading their ideas to millions of listeners. For many young Black men, it became a cultural badge of honor, but it also blurred the line between faith and self-deification.

Black Panther Party (BPP) - Founded in 1966 by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the Black Panther Party wasn’t a religion but a political force. Inspired by Malcolm X, many members rejected Christianity altogether, embracing atheism or skepticism.

The Panthers built “survival programs”, free breakfast for kids, health clinics, and community patrols to protect against police brutality. They became a symbol of resistance, power, and pride. But their rejection of the church meant another generation of Black youth grew up disconnected from Christ.

The Legacy of the BRICs

The BRICs gave Black people identity, pride, and resistance in a time of oppression. They spoke to real pain and offered answers when the church seemed distant. But they also pulled many away from the gospel, replacing Christ with nationalism, mysticism, or self-worship.

Even today, these movements are praised in music, culture, and politics. But their impact, the decline of the Black church, the breakdown of morality, and the confusion of identity still weigh heavily on the community.

The Impact on Black America Today

The ripple effects are still visible:

Over 75% of Black children are born out of wedlock.

Hip-hop culture often glorifies violence, hypersexuality, and rebellion.

Church attendance among Black youth has plummeted.

The breakdown of the family, the rise of alternative religions, and the decline of the church all trace back to the cultural shifts that happened after 1964.

The Black church, once the backbone of the community, lost its central role. And when the church loses its influence, morality, unity, and identity begin to crumble.

Moving Forward: What Can We Learn?

History teaches us that when Christ and the church are at the center of Black life, we thrive. When we drift away, we fall apart.

If Black America wants restoration, in families, in culture, in identity, we must return to the teachings of Christ and rebuild the church as the heart of our communities.

The same God who carried our ancestors through slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation is the same God who can restore us today.